Abstract

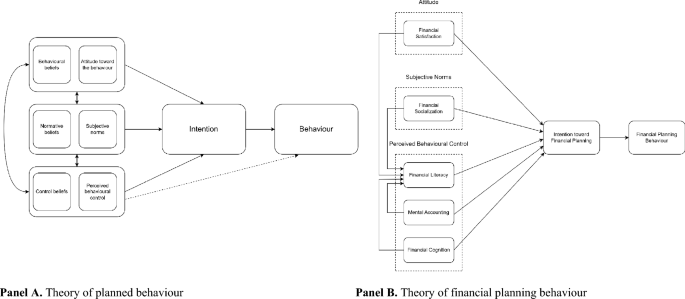

Financial resilience is founded on good financial planning behaviour. Contributing to theorisation efforts in this space, this study aims to develop a new theory that explains financial planning behaviour. Following an appraisal of theories, a systematic literature review of financial planning behaviour through the lens of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) is conducted using the SPAR-4-SLR protocol. Thirty relevant articles indexed in Scopus and Web of Science were identified and retrieved from Google Scholar. The content of these articles was analysed using the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes (ADO) and theories, contexts, and methods (TCM) frameworks to obtain a fundamental grasp of financial planning behaviour. The results provide insights into how the financial planning behaviour of an individual can be understood and shaped by substituting the original components of the TPB with relevant concepts from behavioural finance, and thus, leading to the establishment of the theory of financial planning behaviour, which posits that (a) financial satisfaction (attitude), (b) financial socialisation (subjective norms), and (c) financial literacy, mental accounting, and financial cognition (perceived behavioural controls) directly affect (d) the intention to adopt and indirectly shape, (e) the actual adoption of financial planning behaviour, which could manifest in six forms (i.e. adoption of cash flow, tax, investment, risk, estate, and retirement planning). The study contributes to establishing the theory of financial planning behaviour, which is an original theory that explains how different concepts in behavioural finance could be synthesised to parsimoniously explain financial planning behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background of financial planning

Personal financial planning is critical to maintaining a healthy financial status and fulfilling future financial needs (Mahapatra et al. 2019). In essence, personal financial planning is a process of managing personal wealth to obtain economic satisfaction (Kapoor et al. 2014). This encompasses six areas of financial planning, namely cash flow planning, tax planning, investment planning, risk management, estate planning, and retirement planning (Altfest 2004). Ideally, comprehensive financial planning should involve all six areas. However, the specific life stage of an individual, such as retirees, and life realities, such as retrenchment, may dictate the primary focus and/or relevance of these areas. For example, retirees might not be actively engaged in tax planning, and a retrenched worker might not be in a position to engage in investment planning. More importantly, personal financial planning is a profound concept that theoretically reflects and practically safeguards individuals’ financial resilience, and thus, it can be understood from two unique lenses: academic and practice.

From an academic perspective, the field of personal finance is interdisciplinary; it covers a wide range of areas, including economics, family studies, finance, information technology, psychology, and sociology (Schuchartdt et al. 2007). Different disciplines have varied theories that play a supporting role in understanding individuals’ financial behaviour and money management (Copur and Gutter 2019). However, the theories explaining personal finance are often borrowed rather than created, a situation that is common for emerging interdisciplinary fields (Murray and Evers 1989) such as personal finance (Lyons and Neelakantan 2008), which encompasses close to 250 publications only in Scopus by the end of 2022.Footnote 1

From a practice standpoint, Palmer et al. (2009) argued that it is necessary to develop financial planning for each individual that can deal with the uncertainty of the economic environment. Hanna and Lindamood (2010) echoed that personal financial planning can provide individuals sufficient economic benefits such as increasing wealth, preventing financial loss, and smooth consumption.Footnote 2 However, many individuals lack sufficient financial capability, skills, and knowledge to be able to effectively manage their personal finances (Chen and Volpe 1998).

Problems and importance of financial planning

Over time, the society is facing increasing challenges of high living expenses and various financial difficulties given the constant development of complexity in financial matters (Baker et al. 2023; Mahapatra et al. 2019). Individuals’ ability to manage their personal finances and financial affairs has been gaining attention across the world, wherein being financially healthy gets prioritised by individuals in their lives (e.g. changing investment approach and contributing more to retirement savings to hedge against inflation; Personal Capital 2022).

Birari and Patil (2014) state that individuals should practice and gain basic financial skills to manage their expenditures and acquire well-developed planning to avoid being in financial difficulties. Many factors may lead to irrational financial behaviours from individuals—for example, excess consumption, aggressive trading, lack of savings, and retirement planning. However, one of the major root causes that propels irrational financial behaviour as well as the many financial difficulties that people encounter is inarguably the lack of financial literacy (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development 2020).

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2013), financial literacy consists of financial knowledge, skill, attitude, awareness, and behaviour to make a rational financial decision and achieve individual financial well-being. In other words, financial literacy is the ability to utilise knowledge and skills to manage financial matters effectively (Pailella, 2016; Tavares et al. 2023).

Noteworthily, financial behaviour in individuals’ daily lives cannot be separated from financial literacy. Tan et al. (2011) state that the process of personal financial planning requires individuals to acquire not only cognitive ability but also financial literacy. According to Ali et al. (2014), financial literacy should be given serious attention from individuals because it is able to affect their welfare. Indeed, financial literacy has been proven to have a positive impact on financial planning. Specifically, individuals who lack financial literacy will often end up in debt (Lusardi and Tufano 2009) and will most likely increase their financial burden (Gathergood 2012). By having sufficient relevant information, individuals can analyse their financial situation and make decisions wisely.

Gaps and necessity to theorise financial planning behaviour

As mentioned, extant understanding of financial planning is mainly derived from borrowed theories. While this practice remains acceptable, it is important that new theories are developed to enrich understanding of financial planning, particularly from a behavioural perspective, as the issue of good or poor financial planning is dependent on the individual and his or her financial planning behaviour. With the maturity of the literature on financial planning, the time is now opportune to engage in new theory development (Kumar et al. 2022).

The need for theory development is further accentuated as there is a notable lack of theory development in explaining financial planning behaviour. Noteworthily, existing frameworks and models remain piecemeal and do not fully cover the whole spectrum of financial planning. After an appraisal of theories related to financial planning (“Evolution of theories” Section), the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) has been found to be the most suitable theory on parsimonious grounds (i.e. the capability and capacity of the theory’s core components to act as an organising frame) and its track record of theory spinoffs (e.g. the theory of behavioural control; Lim and Weissmann 2023) to explain an individual’s financial planning behaviour. Therefore, an integration of the respective antecedents, decisions, and outcomes (ADO) to form a new, holistic theory is required to document the complexity and the extent of considerations required to explain financial planning behaviour. Such an integration can and will be pursued via a systematic literature review (Lim et al. 2022a, b).

Goals and contributions of this study

The goal of this study is to establish a formal theory to explain financial planning behaviour. To do so, a systematic literature review is conducted, wherein the SPAR-4-SLR protocol is adopted to guide the review process, whereas the antecedents, decisions, and outcomes (ADO) framework (Paul and Benito 2018) and the theories, contexts, and methods (TCM) framework (Paul et al. 2017) are adopted and integrated to analyse the findings of the review—a best practice demonstrated and recommended by Lim et al. (2021). In doing so, this study makes two noteworthy contributions.

From a theoretical perspective, the integrated framework contributes to integrate fragmented knowledge and reduce the production of isolated knowledge on financial planning behaviour. In addition, the framework clarifies the state of existing insights and empowers the discovery of new insights on financial planning behaviour. Certainly, insights gathered from a well-structured framework can provide a better start to add to existing knowledge and increase growth in the field (Kumar et al. 2019; Lim et al. 2022a, b). More importantly, the nomological structure of the framework also enables the study to establish a new theory called the theory of financial planning behaviour, which can act as a multi-dimensional behavioural guideline that involves planning, developing, and assessing the operation of cash flow, tax efficiency, investment planning, risk management, estate planning, and retirement planning within an individual.

From a practical standpoint, the insights from the study are expected to contribute to future financial service professionals gaining advantages in the understanding of financial planning behaviour in catering to the future needs of the public. Additionally, policymakers would benefit from utilising the information to effectively provide financial education programs to enhance individuals’ financial well-being. Further implications for this study focusing on consumers and managers are also discussed towards the end of this study.

Theoretical background

Evolution of theories

Over the past decades, several theories have been used by researchers on financial planning and the determining factors that influence it. The evolution of theories relating to financial planning is based on the concept of behavioural finance. These theories remain important in financial planning research (Asebedo 2022; Overton 2008). The most well-known theory related to behavioural finance is the TPB (Ajzen 1991). It has been widely used on different research topics to predict and explain individuals’ behaviour or the insufficient control of their behaviour (Ajzen 1985, 1991, 2002). Noteworthily, the TPB is an extension of the theory of reasoned action, which suggested that human behaviour is determined by the intention to perform a certain behaviour, whereby the intention can be determined by attitudes and subjective norms (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975).

In addition, Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs has been used by Chieffe and Rakes (1999) to identify and rate the different segments of financial services best suited to each level of income group. The hierarchical approach of this theory provides a framework that explains different financial planning services related to each income group. According to Xiao and Noring (1994) and Xiao and Anderson (1997), the notion of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs clearly explains an individual’s financial needs in the form of a hierarchy. The framework of a hierarchical form of financial planning indicates that individuals would only strive for a high level of financial needs after a lower level of financial needs is met. It is recommended for individuals to fulfil their needs step by step to avoid facing financial difficulties.

Another theory that has been applied to financial planning is the life-cycle hypothesis (Modigliani and Brumberg 1954), which is an economic theory that explains an individual’s saving and spending behaviour throughout their lifetime. The theory also points out that individuals want to have smooth consumption by saving more if their income increases and borrowing more when their income ceases. Shefrin and Thaler (1988) state that individuals mentally place their assets into three different accounts, which are current income, current assets, and future income. According to Modigliani and Brumberg (1954), this theory assumes that individuals will fully utilise their utility for future consumption and aim to accumulate savings and resources for future consumption after retiring. The model explains that individuals’ consumption and saving decisions are formed from a life-cycle perspective. Such individuals will begin with low income when they start working, and their income will slowly increase until it reaches a peak level. Taking a behavioural enrichment (or behaviourally realistic) perspective of the life-cycle theory, Shefrin and Thaler (1988) state that the behavioural life-cycle hypothesis includes mental accounting, self-control, and framing, which represent three important behavioural features that are usually missing in the economic perspective of the traditional life-cycle theory. The authors mention that individuals use mental accounting to control their propensity to spend on their assets. The willingness to spend is usually related to their current income. According to Warneryd (1999), individuals usually have a specific method to mentally allocate their expenditures into different accounts. In addition, the marginal propensity to save and consume will be different in each account. According to Shefrin and Thaler (1988), individuals may face difficulties in controlling their spending, and thus, these individuals may form personal behavioural incentives and constraints. For example, individuals would possess the intention to save and create assets when constraints are available. They also explain that individuals’ preferences are not fixed but vary depending on the constantly changing economic environment and social stimuli (Duesenberry and Turvey 1950; Katona 1975). Furthermore, the life-cycle theory faces some challenges while explaining individuals’ behaviour, such as assuming that individuals will act rationally, be consistent, and make wise intertemporal choices throughout their lifetime (Deaton 2005). The life-cycle theory explains that individuals’ saving decisions are based on their preferences for either present or future consumption. The theory also assumes that individuals determine a desirable age of retirement and level of consumption to fully utilise their utility throughout their lifetime.

Prospect theory is an economic theory that assumes individuals treat losses and gains differently, showing how an individual decides among several choices that involve uncertainties (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). This theory explains that their decisions are easily affected by psychological factors and that they are logical decision-makers. However, when individuals decide on whether to purchase or not, they are most likely affected by their cognitive biases. The theory also postulates that making losses will cause a larger emotional impact on individuals rather than a comparable amount of gain. Thus, individuals will prefer choosing the option with perceived gains. For example, individuals would prefer the option of a sure gain instead of a riskier option with a chance of receiving nothing or making a loss. Hence, the theory summarises that individuals are mostly loss averse when they face several choices. Individuals are more sensitive towards losses and would most likely prefer avoiding losses and prefer sure wins. This can be explained by the fact that the emotional impact of losses on an individual is greater than an equivalent gain.

The financial capability model is another prominent theory. Financial capability, which has been gaining prominence across the globe, is defined as the capability and skills of individuals to make rational and effective judgements on managing their financial resources (Noctor et al. 1992). Nowadays, individuals have been urged to ensure that they acquire sufficient resources for their retirement and provide a financial safeguard for any sudden occurrence. According to Atkinson et al. (2007), the financial capability model has been studied and is related to individuals’ financial behaviour, attitude, and knowledge. The researchers identified five different components under the financial capability model: (1) making ends meet (managing personal financial resources, i.e. individuals who have acquired financial knowledge skill sets can finance their resources well and meet financial goals); (2) keeping track (managing money, i.e. planning and recording personal daily expenses to avoid overspending); (3) planning ahead (this helps individuals to be future oriented, i.e. always planning and managing their financial resources to be prepared for any financial uncertainties in the future); (4) choosing products (accumulating resources and managing different assets’ risks, i.e. making a rational decision in choosing financial products and diversifying risks); and (5) staying informed (being updated and studying financial matters in the current market and economy, i.e. individuals have to be eager to keep track on financial matters happening in the market, such as changes in the overnight policy rate (OPR) and stock market movement).

After a review of all the theories (Table 1), the TPB has been found to be the most suitable theory to serve as a foundational lens for a review on financial planning behaviour with the aim of establishing a new theory in this field. Unlike the other theories (e.g. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, life-cycle hypothesis including behavioural life-cycle hypothesis, financial capability model, prospect theory), the TPB is an adaptable yet parsimonious theory that has a track record of spinning off new theories (e.g. the theory of behavioural control; Lim and Weissmann 2023). Noteworthily, the TPB can be applied to financial behaviours (Bansal and Taylor 2002; East 1993; Xiao and Wu 2006), wherein the three antecedents of the TPB (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control) are found to be associated with intention and contribute to financial behaviour (Shim et al. 2007; Xiao et al. 2007). Unlike other theories, the mediating effect of financial literacy, which provides an important lens to understand good and poor financial planning, can be applied to the TPB to explain an individual’s intention on financial behaviour. More importantly, it is necessary to understand how the TPB can further explain individuals’ behaviour before examining financial literacy through a behavioural approach. The theory assumes that intention is the best factor to predict an individual’s behaviour, which, in turn, is examined by attitude and social normative perceptions towards an individual’s behaviour (Montano and Kasprzyk 2015). Furthermore, individuals’ experiences normally affect their financial decision-making and the way they manage their personal finances. Therefore, financial literacy can be explained as an individual’s confidence and capability to make full use of their financial knowledge (Huston 2010) and manage financial matters (Lusardi and Mitchell 2014), which they would have perceived control over. In this regard, the theory can be applied to examine how the financial literacy process works on each individual. Moreover, Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) explain that the favour of financial literacy is more than that of financial capability, where individuals are responsible for their own financial decisions. Hence, financial literacy acknowledges the perceived control of individuals on their financial decisions. That being said, an individual will only show positive financial behaviour when they perceive the value of their behaviour based on their attitude. Therefore, financial behaviour will not be decided based on their financial knowledge but based on their attitude, which is the main component of this theory. In other words, the evaluation of financial knowledge will be better captured through the components of the TPB (e.g. perceived behavioural control), though conceptual contextualisation is necessary to better resonate with the financial planning behaviour of individuals. To aid this task, the next section provides a deeper discussion to understand the fundamental tenets of the TPB.

Theorisation of the theory of planned behaviour

According to Xiao (2008), the TPB is one of the best and most suitable theories related to financial behaviour that studies and predicts human behaviour. In essence, the TPB is an extension of the theory of reasoned action, which initially posits that attitude and subjective norms shape the intention to perform a behaviour, which, in turn, predicts the actual performance of that behaviour (Ajzen 1991). However, behavioural intention does not always translate into behavioural performance (Lim and Weissmann 2023), which is the main reason why the TPB was proposed to overcome the limitation of the theory of reasoned action, with the inclusion of perceived behavioural control in the TPB as a mechanism to recognise the volitional control that individuals possess in translating or not translating behavioural intention into behavioural performance (Ajzen 1991, 2002).

Perceived behavioural control can be expressed as follows: Given an individual’s available resources and choices, how easy or hard it is to display a certain behaviour or act in a certain way? In this regard, the performance of an individual’s behaviour depends on his or her ability to act on said behaviour (Ajzen 1991). The TPB posits that the perceived control on certain behaviour will be greater when the individual has greater resources (social media, money, time) and choices (Lim and Weissmann 2023). Indeed, several researchers have found that perceived behavioural control has a positive relationship with intention and behaviour (Fu� et al. 2006; Lee-Patridge and Ho 2003; Mathieson 1991; Shih and Fang 2004; Teo and Pok 2003).

Subjective norms can also be used to predict individual behavioural intention. As one of the original components of the theory of reasoned action, subjective norms refer to social influence and the social environment affecting an individual’s behavioural intention (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). It is defined as an individual’s perception of the possibility that social agents approve or disapprove a behaviour (Ajzen 1991; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). It focuses on everything around individuals, such as social networks, cultural norms, and group beliefs. This is known as a direct determinant of behavioural intention in the theory of reasoned action and the TPB. Through the lens of subjective norms, an individual is said to be willing to perform a certain behaviour even though he or she does not favour performing such behaviour while being under social pressure and social influence (Venkatesh and Davis 2000). Kuo and Dai (2012) state that as subjective norms become more positive, an individual’s behavioural intention to perform or act on a certain behaviour becomes more positive. Several studies have shown a significant relationship between subjective norms and intention (Chan and Lu 2004; May 2005; Teo and Pok 2003; Venkatesh and Davis 2000). Sharif and Naghavi’s (2020) research on family financial socialisation also finds that the behaviour of acquiring relevant norms and information on financial socialisation is associated with subjective norms. The informational subjective norms are known to predict perceived information. Ameliawati and Setiyani (2018) mention that subjective norms in the TPB represent financial socialisation. Their study describes subjective norms as financial socialisation to research the influence of financial management behaviour. In addition, the research of Jamal et al. (2015) on the effects of social influence and financial literacy on students’ saving behaviour used the TPB to develop the model. The author uses subjective norms to represent the social pressures influencing students’ intentions to save. It analyses the influences of parents and peers on the impact on the students’ saving behaviour. Hence, subjective norms have a significant effect on the intentions of individuals towards financial planning behaviour.

Attitude has been identified as a construct that guides an individual’s intention, which results in them acting on a particular behaviour. In essence, attitude can be defined as the evaluation of the positive and negative effects on individuals performing an act or behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975), and by extension, reflects the individual’s belief in certain behaviours or acts that contribute positively or negatively to a person’s life (Ajzen and Fishbein 2000). There are two components of attitude: the attitude towards a physical object (money, savings, pension) and the attitude towards behaviour or performing a certain act (using savings or money to practice financial planning). Keynes (2016) and Katona (1975) state that most individuals possess positive attitudes towards personal saving. Many studies have determined a significant relationship between attitudes and intention (Lu et al. 2003; Ramayah et al. 2020; Wu and Chen 2005). Therefore, attitude can be one of the most important factors to determine and predict human behaviour (Ajzen 1987). According to Xiao (2008), the more favourable the attitude of an individual on performing a behaviour, the easier it is for the individual to perform the behaviour and the stronger the behavioural intention. Further understanding of an individual’s attitude can help to predict their intention and behaviour.

Intention can be defined as an individual’s perception of performing a particular act or behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). In this regard, intention is said to produce a direct effect on an individual’s behaviour as it signals the willingness of an individual to act (Ajzen 1991). The TPB explains that the degree of intentions that are converted into behaviour is determined by the amount of volitional control. Behaviour such as saving money is not considered as full volitional control given the lack of resources and opportunities able to affect the capability to perform the behaviour. While individuals can control their behaviour, their actual behaviour can easily be predicted by their intention accurately, but this does not prove that the measure of correlation is perfect between intention and behaviour (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). Moreover, strong bias always exists in individuals, where they will overestimate the possibility of acting on desired behaviour and underestimate the possibility of acting on undesired behaviour. This can cause inconsistencies between intention and behaviour (performing an actual action) (Ajzen et al. 2004). Behaviour and intention will show high correlation whenever the interval time between them is low (Fishbein and Ajzen 1981). Yet, intention is known to change over time, and thus, if the interval between intention and behaviour is greater, the possibility of change in intention is higher (Ajzen 1985).

Behaviour refers to an observable response to a specific target (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975). In essence, the performance of a given behaviour is a direct outcome of the intention to perform that behaviour as well as an indirect result of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control (Ajzen 1991), as discussed above.

The TPB has been widely used in different fields of research over the past decades: medicine (Hagger and Chatzisarantis 2009; McEachan et al. 2011), marketing and advertising (King et al. 2008; Yaghoubi and Bahmani 2010), tourism and hospitality (Han 2015; Quintal et al. 2010), information science (Lee 2009; Shih and Fang 2004), and, last but not least, human behaviour (Kobbeltvedt and Wolff 2009; Perugini and Bagozzi 2001). All the studies listed above have concluded on the positive and significant effect of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control on an individual’s intention to act on behaviour. In the financial context, Shih and Fang (2004) apply the TPB to an individual’s financial decisions regarding internet banking. The study concludes that the TPB can be successfully applied to understand an individual’s intention to use internet banking. Lau et al. (2001) and Lee (2009) also apply the TPB to study investors’ intentions on online banking and trading online. To provide a more accurate account for financial planning behaviour, a systematic literature review is conducted and reported in the next sections.

Methodology

Study approach: systematic literature review

This study conducts a systematic literature review to develop comprehensive insights into financial planning behaviour based on the TPB. As mentioned above, the TPB is the extension of the theory of reasoned action, and it strongly posits that an individual’s behaviour is determined by the three factors (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control) and is backed by their behavioural intention (Ajzen 1991).

A systematic literature review is known as a ‘research synthesis’, an extensive process of summarising primary research based on an explicit research question, where it attempts to identify, select, synthesise, and assess all the evidence by providing answers to the research question (Donthu et al. 2021; Lim et al. 2022a, b). In this regard, systematic literature reviews not only summarise and synthesise existing knowledge but also facilitate knowledge creation (Kraus et al. 2022; Mukherjee et al. 2022). Moreover, systematic literature reviews gathered eligible and pertinent evidence based on a preset criterion to answer a specific research question, and thus, a transparent and explicit systematic methodology can be used for systematic literature reviews to analyse and reduce biases (Harris et al. 2014; Paul et al. 2021).

Systematic literature reviews can be conducted through various methods. Generally, systematic literature reviews can be domain-based, theory-based, and method-based (Palmatier et al. 2017; Paul et al. 2021). In this study, a theory-based review was used for new theory development. Specifically, the theory-based review is chosen over the other approaches because it serves the purpose of analysing a specific role played by a theory in a given field. One of the examples given by Hassan et al. (2015) is the role of the TPB in the field of consumer behaviour. In this study, the TPB was applied to financial planning behaviour.

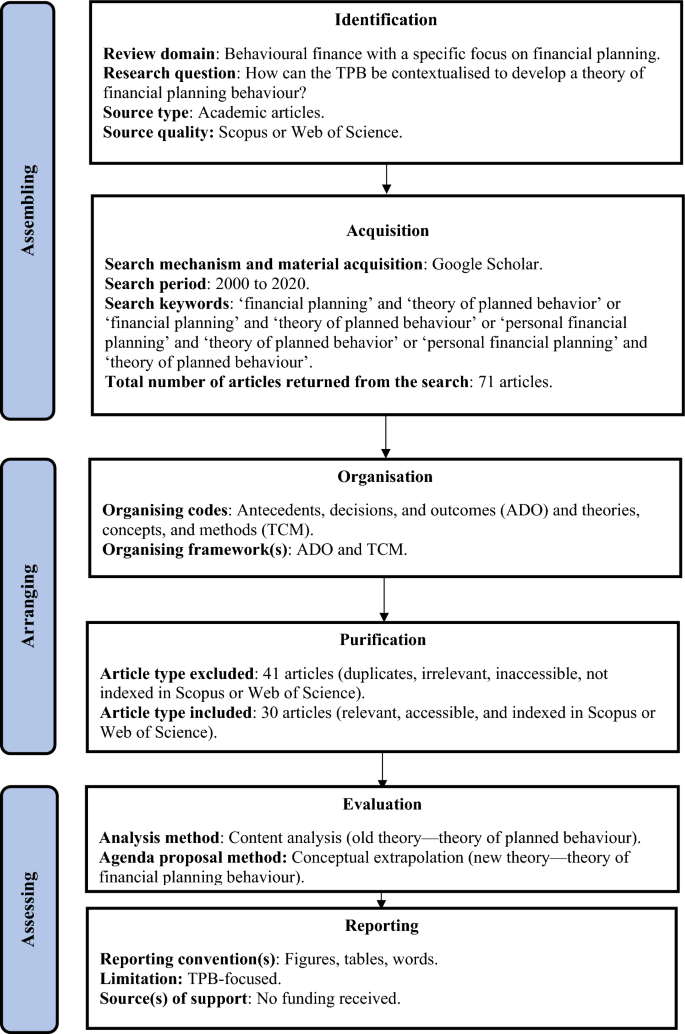

Study procedure: SPAR-4-SLR

Few protocols exist for systematic literature reviews. The most common protocol used by researchers in conducting systematic literature reviews is the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) by Moher et al. (2009). PRISMA is a comprehensive protocol that helps researchers to develop systematic literature reviews. It gathers and reports decisions that researchers have justified from their reviews. However, an uprising protocol was proposed by Paul et al. (2021) to address the existing limitations of PRISMA, namely the Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews protocol or the SPAR-4-SLR protocol. As shown in Fig.� 1, the protocol consists of three stages and six sub-stages, followed by sequences.

-

(1)

Assembling This stage constitutes the (1a) identification and (1b) acquisition of literature that is yet to be synthesised.

-

(2)

Arranging This stage entails the (2a) organisation and (2b) purification of literature in the stage of being synthesised.

-

(3)

Assessing This stage reflects the (3a) evaluation and (3b) reporting of literature that has been synthesised.

Systematic reviews assembling, arranging, and assessing the literature according to the SPAR-4-SLR protocol are expected to: (1) provide significant insights and (2) stimulate nuanced agendas for knowledge advancement in the review domain. Substantially, by providing such significant insights and agendas using the SPAR-4-SLR protocol, (1) the review is comprehensively justified for logical and pragmatic reasons, and (2) each stage and sub-stage is reported with full transparency.

The researchers begin with assembling in the (1a) identification stage, identifying the research domain and research question. The research domain of this study is behavioural finance with a specific focus on financial planning. The research question of this study is ‘How can the TPB be contextualised to develop a theory of financial planning behaviour?’ Thus, academic articles selected should focus on financial planning (i.e. the focus of this review) and the TPB (i.e. the theory contextualised for this review). The source quality was established based on Scopus or Web of Science indexing in line with Paul et al. (2021). Moving on to the (1b) acquisition stage, the search mechanism will rely on Google Scholar, which is free and can be easily accessed for article search.Footnote 3 The search period will begin from 2000 to 2020 (20� years) as most articles on the TPB and financial planning behaviour started to appear in the early 2000s. Related articles searched between these years are included in this study. The search was conducted multiple times with different keywords based on American and British spelling as well as different combinations: (1) ‘financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behavior’, (2) ‘financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behaviour’, (3) ‘personal financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behavior’, and (4) ‘personal financial planning’ + ‘theory of planned behaviour’.Footnote 4

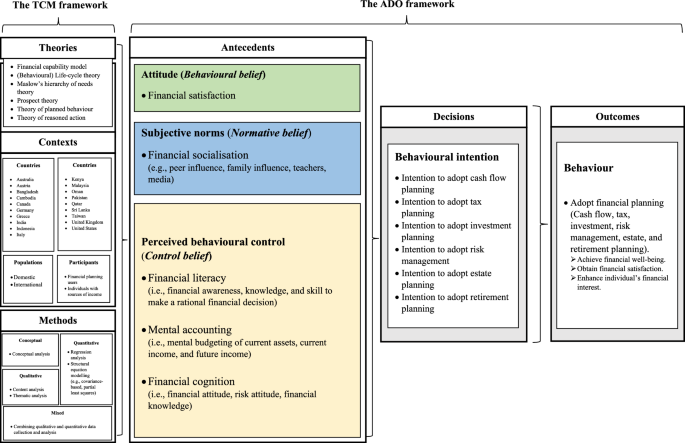

Next, the researchers move onto arranging in the (2a) organisation stage, wherein the organising code for this study is ADO and TCM, which rely on the suggested frameworks used, the ADO framework (Paul and Benito 2018; Pansari and Kumar 2017) and the TCM framework (Paul et al. 2017). Refer to Fig.� 2 for the overview of ADO on the insights of the TPB on financial planning behaviour and its supporting TCM. In the (2b) purification stage, the articles gathered are filtered in this process. The researchers decided which articles to include and exclude from the study. The criteria to exclude articles in this stage include duplicate articles, irrelevant articles, inaccessible articles, and lastly, non-journal-title articles; 41 articles were excluded based on the criteria, and 30 articles proceeded to the next stage.

Finally, the researchers move into assessing in the (3a) evaluation stage, which involves the analysis and the agenda proposal. The study utilised content analysis, a methodical approach for coding and interpreting textual data from the selected articles to draw meaningful conclusions (Kraus et al. 2022). This systematic technique, which was executed by one author (a doctoral scholar) and cross-validated by another author (a senior academic) with an intercoder reliability of ± 95% and differences clarified and resolved, enabled the researchers to identify, categorise, and analyse patterns within the text, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter (Patil et al. 2022). The theory development and future research agenda were formulated through conceptual extrapolation and sensemaking (i.e. scanning, sensing, and substantiating) (Lim and Kumar 2023). This process entailed critically examining the existing theories, extracting key concepts, and extrapolating these to propose new research directions. Thus, this study provided a roadmap for future studies, fostering further evolution in the field of financial planning behaviour. In the (3b) reporting stage, the reporting conventions used include figures, tables, and words. No ethical approval is required since the review is based on accessible secondary data (journal articles), which can be accessed by anyone with subscription (Lim et al. 2022a, b).

Results

Profile of TPB and financial planning behaviour research

The systematic review of 30 articles covered different insights into the existing research of the TPB and financial planning behaviour, covering the six components of financial planning (i.e. cash flow planning, tax planning, risk management, investment planning, estate planning, and retirement planning) (Fig.� 2). Appendix 1 summarises the articles in Appendix 2 based on the approaches of Paul and Mas (2019) and Harmeling et al. (2016). The articles are classified based on author citations, years, number of citations, methods, sample, related financial planning components and variables, and lastly findings. The findings of each article briefly explained how the construct of the TPB is a predictor or shows a significant effect on financial planning behaviour.

Based on this review, which begins from 2000 to 2020, the past two decades of research in the field of behavioural economics (later known as behavioural finance) have been on continuously identifying and explaining an individual's finances from an extended social science perspective, which includes psychology and sociology. Behavioural finance can be defined as the field of study where psychological factors affect an individual's financial behaviour (Shiller 2003). The combination of the TPB and financial planning has proven to be impactful with over 3000 citations among the 30 articles. The articles utilised four different methods: the quantitative approach (n = 24), the qualitative approach (n = 3), the mixed method approach (n = 1), and the conceptual approach (n = 2).

Lastly, the TPB (i.e. attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioural control, and behavioural intention) has been found to be a good predictor of financial planning behaviour (i.e. cash flow planning, tax planning, risk management, investment planning, estate planning, and retirement planning) and possesses positive relationships with each component of financial planning. For example, the TPB was found to be positively related to the intention to invest, mental budgeting behavioural intention, influencing savings and investment, and the intention to prevent risky credit behaviour, among others.

Contextualising the TPB for financial planning behaviour

Table 2 and Fig.� 3 show the contextualisation of the TPB for financial planning behaviour, leading to the establishment of the theory of financial planning behaviour. Pansari and Kumar (2017) suggest the use of such a table to compare and explain each construct of the framework. The table, which leverages the findings from the review depicted in Fig.� 2, clearly illustrates how the TPB can be contextualised to explain financial planning behaviour. Attitude can manifest as financial satisfaction, wherein individuals who are dissatisfied, not fully satisfied, or wish to be more satisfied with their financial state will develop a positive disposition towards financial planning. Subjective norms can manifest as financial socialisation, wherein individuals learn about societal expectations of financial planning when they socialise with others (e.g. family, friends, work colleagues). Perceived behavioural control can manifest as financial literacy, mental accounting, and financial cognition, wherein the effect of financial satisfaction and financial socialisation is mediated through financial literacy, which may be shaped by the capability to perform mental accounting and the capacity for financial cognition. These factors can collectively shape the individual's intention to engage in financial planning, which, in turn, motivates the actual behaviour of engaging in financial planning, which can take six forms, namely cash flow planning, tax planning, investment planning, risk management, estate planning, and retirement planning.

Reflections and ways forward

Behavioural decision-making has been one of the most significant research interests for economists over the past decades. Past researchers (Xiao and Wu 2006; East 1993; Bansal and Taylor 2002) have applied the TPB to financial behaviour. The three antecedents of the TPB (attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control) were found to be associated with the intention of an individual and contribute to financial behaviour (Shim et al. 2007; Xiao et al. 2007). Unlike other theories, the mediating effect of financial literacy can be applied to the TPB to explain financial behaviour intentions. The variables of mental accounting and financial cognition were not frequently used by the researchers in the study of financial planning, while in this study, both variables are positioned as relevant components of perceived behavioural control in the TPB.

The concept of mental accounting has been extensively studied in the research area of psychology on financial decisions (Mahapatra and Mishra 2020). However, past studies on mental accounting in financial planning are insufficient. The formation and influences of mental accounting as a cognitive process—which consists of the concepts of current income, current assets, and future income as well as mental budgeting—play an important role in the personal financial planning process to each individual. It serves as a guideline in the process of financial planning and provides useful insights. Budgeting plays a key role in managing the financial life of an individual in terms of short-term (e.g. prioritising spending in different categories) and long-term (e.g. setting aside money for investment and future use) financial planning.

Previous research has applied mental accounting with the theory of the behavioural life-cycle model. Shefrin and Thaler (1988) mentioned that people mentally divide their incomes into current income, current assets, and future income, where the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) for each account is relatively different. Mental accounting is helpful and crucial for individuals to plan for their future financial needs so that they can deal with any unexpected financial difficulties in the future. However, there are still gaps to fill to come out with optimal financial decisions. Therefore, given the need of individuals for personal financial planning, it is necessary to apply mental accounting to each individual by determining their spending and saving tendencies.

Moreover, the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic have also taught the world painful lessons; the need for financial literacy and cash flow control has been highlighted and considered by the public. A study conducted by Shahrabani (2012) on the effect of financial literacy and intention to control personal budget concludes that individuals with high levels of financial knowledge and literacy can influence the intention to have budgetary control. The study shows a positive relationship between the intention to budget and financial knowledge. Selvadurai and Siraj (2018) study financial literacy education and retirement planning in Malaysia. The authors mention that mental accounting is closely related to financial literacy education. Financial literacy can enhance mental accounting as it affects the behaviour of an individual in planning their savings and expenditure. In particular, individuals who acquire financial literacy education are most likely able to control their expenditure by not spending more than their income, which results in having sufficient savings in the long run. The relationship between mental accounting and financial literacy has been proven to be indispensable.

Cognitive ability also plays an important role in financial literacy as it entails understanding financial knowledge and the ability to perform with available resources. While the relationship between financial cognition and financial literacy is strong, individuals can use their cognitive abilities to solve financial problems. Yet, the cognitive biases exist and influence financial decision-making. Agarwal and Muzumder (2013) state that individuals with no cognitive ability are most likely to face difficulties while making financial decisions. Also, individuals must at least acquire good memory skills, conceptual ability, and financial sophistication to be involved in financial activities. According to Fu et al. (2010), understanding the attitude of an individual enables one to predict their intentions and behaviour. This could also influence the formation of their attitude. Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) mention that cognitive abilities are a significant component of financial literacy to determine desirable financial decision-making. In the case of financial literacy, a link between cognitive abilities and the adaptability of financial decision-making has been studied extensively in the field of personal finance. An individual must acquire cognitive skills to make a sound financial decision in an effortless way, which consists of the ability to recall and utilise financial knowledge (memory) and to implement various numerical operations (numeracy) (Chirstelis et al. 2010; McArdle et al. 2009). Three variables were discussed under the model of financial cognition: financial attitude, risk attitude, and financial knowledge.

Based on the information mentioned above, the mediating effect of financial literacy on mental accounting and financial cognition is indispensable. Policymakers and researchers should work on improving financial literacy and forming positive financial behaviours. Several studies have proven that financial literacy has slowly become a significant component of rational financial decision-making and that it also provides implications for financial behaviour. Individuals or families with higher levels of financial literacy will have an advantage compared to others and higher wealth accumulation as they have the knowledge and skills to participate in financial activities (Schmeiser and Seligman 2013). Past studies have proven that financial literacy plays a remarkable role in determining financial outcomes in terms of the components of financial planning (Hilgert et al. 2003). Hence, the need for financial literacy in financial planning is indispensable, and it should be considered by individuals as it affects their welfare.

However, no one has attempted to contextualise the TPB and financial planning with the variable of mental accounting and financial cognition with the mediating effect of financial literacy to understand and determine financial behaviour. Thus, this new theory clarifies the conceptualisation and operationalisation of the theory of financial planning behaviour between the variables of mental accounting and financial cognition, and, most importantly, the mediating effect of financial literacy. However, the new theory, in its present and encompassing form, has yet to be tested empirically, and therefore, this warrants future research across different financial products across countries and populations to establish its generalisability.

Discussion and conclusion

This study developed a new theory called the theory of financial planning behaviour using the TPB of Ajzen to understand the financial behaviour of individuals in managing their personal finances. This study examines how the TPB can be contextualised into a theory that more relevantly explains financial planning behaviour. The theoretical background section of this study presents a comprehensive review of the evolution of theories as well as theorisation for the TPB. With a systematic review of the literature, it can be concluded that the constructs of the TPB can be contextualised to better explain financial planning behaviour—that is, the review results showed how different concepts and factors affect the financial planning of an individual by substituting the original components of the TPB with financial variables. Moving on, this study concludes with an articulation of its implications for academics, consumers, and managers.

Implications for academics

The main theoretical contribution of this study is the establishment of the theory of financial planning behaviour. Noteworthily, this new theory represents a noteworthy attempt to demonstrate how a grand theory such as the TPB can be contextualised and thus transformed into a new theory that resonates with realities in the field, in this case, financial planning. The systematic literature review methodology has also proven itself as a useful approach to source for scholarly evidence to offer preliminary support for the new theory.

Another noteworthy contribution is the extrapolation of perceived behavioural control, which answers the call by Lim and Weissmann (2023) to identify or source for new forms of behavioural control, going beyond the traditional psychological conceptualisation of self-efficacy. Through this study, three types of perceived behavioural control were revealed: financial literacy, mental accounting, and financial cognition. Moreover, the interdependent relationships between these three forms of perceived behavioural control were also identified and theorised, wherein the capability of mental accounting and the capacity for financial cognition shape the financial literacy of the individual, which, in turn, mediates the effects of financial satisfaction (attitude) and financial socialisation (subjective norms) on that individual’s intention and actual behaviour to engage in financial planning.

For researchers seeking to apply the theory of financial planning behaviour in a study, they might operationalise the variables in the following way. Financial satisfaction, financial socialisation, and financial literacy could be assessed using the scales validated by Madinga et al. (2022). Financial cognition and mental accounting, being somewhat newer constructs in the literature, might require the development of new scales, which could be validated through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. For data analysis, researchers might employ a structural equation modelling (SEM) approach to test the relationships between these constructs, as SEM allows for the simultaneous examination of multiple relationships among observed and latent variables. This technique also enables researchers to test the mediating role of financial literacy in the relationship between financial satisfaction, financial socialisation, and financial planning behaviour, thereby assessing the robustness of the proposed theory. If researchers are interested in examining the moderating effects of certain variables (e.g. age, education, or household income), they could use moderation analysis to determine whether the strength or direction of these relationships varies under different conditions.

To this end, the theory of financial planning behaviour should serve as a useful foundational theory to understand a myriad of individual financial planning behaviour such as cash flow planning, tax planning, investment planning, risk management, estate planning, and retirement planning. In this regard, future research is encouraged to explore for new mechanisms that can positively influence or strengthen the variables espoused by the new theory, such as financial satisfaction (e.g. mechanisms that can prompt individuals to evaluate their financial satisfaction—e.g. advertising), financial socialisation (e.g. platforms to encourage individuals to socialise within a financial setting—e.g. metaverse and social media groups), and financial literacy (e.g. ways to enhance mental accounting capability and financial cognition capacity). Nonetheless, this study does not discount the possibility of discovering additional attitudinal, normative, and control variables, which could lead to possible extensions to the theory of financial planning behaviour, as in the case witnessed by TPB. Thus, the new theory herein is intended to inspire new ideas, not to limit them.

Implications for consumers

This study reaffirms the importance of financial planning to safeguard financial resilience in individuals' daily lives. Adopting financial planning entails endless benefits for consumers who do so. Noteworthily, it is important to determine short-term and long-term financial goals and to achieve them via financial planning. Having these goals in mind can provide a sense of direction and purpose in life.

This study is important for all consumers who wish to make ideal financial decisions. Consumers may adopt better cash flow management by implementing financial planning to have a stable financial flow. A cash flow plan can provide an estimation of future income and expenses to achieve financial efficiency and create an emergency fund. Hence, implementing financial planning may help to relieve financial stress and plan for future needs.

Also, consumers can not only gain monetary benefits but also improve their financial literacy. The world has slowly become more financialised, where financial products have developed rapidly and become more complex (Kumar et al. 2023; Goodell et al. 2021), which requires consumers to be financially literate before making ideal financial decisions (She et al. 2023; Bannier and Schwarz 2018). Thus, financial institution managers and policymakers are working on improving the financial literacy of consumers and forming positive financial behaviour.

Indeed, financial literacy is a significant component of rational financial decision-making, and it also provides implications towards financial behaviour. Individuals or families with higher levels of financial literacy will have an advantage compared to others as well as higher wealth accumulation as they have the knowledge and skills to participate in financial activities.

Crucial to developing financial literacy is the capability to do mental accounting and the capacity for financial cognition. That is to say, consumers must seek financial education, be it formally or informally, so that they are able to identify and evaluate the different options for financial planning. Similarly, consumers should allocate adequate resources (effort, time) to think about financial planning, which is not a low but rather high involvement process.

Implications for managers

Promoting financial planning has always been a major challenge for financial managers. The newly established theory of financial planning behaviour emerging from the grand TPB can be put into practice by authorities. The findings of this study can be used by financial managers to understand the financial planning behaviour of consumers.

Based on the results and implications of past studies, introducing financial planning behaviour can benefit banks as well as investment and insurance companies that aim to promote consumer financial well-being. It can provide insights into how different factors affect the intention and adoption of financial planning.

Financial literacy needs to be considered as it is an important mediating factor that influences the intentions and behaviour of consumers. For example, whenever a bank introduces financial products to a prospect, that bank must ensure that the prospect is financially literate or else provide sufficient financial knowledge before the prospect develop a financial plan or purchase any financial product from that bank. This is to ensure that their customers possess knowledge of and clarity on the program or product.

In addition, financial institution managers are encouraged to focus on factors (i.e. mental accounting, financial cognition, financial socialisation, financial satisfaction, and financial literacy) that influence customer behaviour towards financial planning before implementing financial programs. For example, understanding the budgeting styles and minimum level of financial satisfaction of customers may help to develop relevant and applicable financial plans for them. Consider a middle-aged client, John, who has recently experienced a job loss. John is feeling uncertain about his financial future and seeks advice from a financial advisor. The financial advisor, following the theory of financial planning behaviour, would first evaluate John's financial literacy level to assess his understanding of financial products and concepts. Then, the advisor would use the theory's constructs such as mental accounting (how John organises his finances and prioritises spending), financial cognition (how John understands his financial situation), and financial satisfaction (how content John is with his current financial state) to develop a comprehensive financial plan. For instance, the financial advisor may realise that John's financial cognition is low, indicating a lack of understanding of the severity of his financial situation. Therefore, to improve his financial cognition, the advisor would emphasise financial education and assist John in developing better mental accounting habits, such as setting up separate 'pots' for his savings, expenses, and investments. This approach is aligned with promoting financial literacy and ensuring the client's knowledge and clarity on his financial plan, which are aspects underscored in our theory.

Implications for policymakers

The findings of this study serve to inform and guide policymaking in significant ways. Policymakers play a crucial role in shaping the financial landscape that influences financial planning behaviour. A key aspect is the importance of financial literacy, which suggests that national education policies should incorporate financial education from early learning stages. Special focus should be given to underprivileged and marginalised communities, who may lack access to financial literacy resources. This might involve legislation mandating financial institutions to fund these education programs as a part of their corporate social responsibility.

This study also illuminates the role of mental accounting and financial cognition in financial planning behaviour. This could inspire policymakers to collaborate with technology developers to create user-friendly digital tools and applications that promote mental accounting practices. Such initiatives should be supported by national policies encouraging technological innovation in the financial sector.

Furthermore, the impact of financial satisfaction on financial planning behaviour underscores the need for regulation in financial advertising. Policymakers should ensure that financial advertising does not create unrealistic expectations that lead to dissatisfaction, and transparency should be mandated, with severe penalties for institutions found to be misleading consumers.

Moreover, the study's findings encourage the creation of financial socialisation platforms. Policies should support the development of both online and offline platforms for learning, sharing, and discussing financial planning strategies and experiences. Policymakers should work with technology companies, local communities, and financial institutions to ensure these platforms are safe, accessible, and inclusive.

Lastly, the responsibility of policymakers extends to the protection of citizens from unfair financial practices. Legislation should ensure transparency in financial markets, particularly regarding fees, interest rates, and risks associated with financial products. Policymakers may also consider mandating financial counselling for complex financial decisions, such as mortgages or large investments, to increase financial satisfaction.

Limitations and future research directions

Notwithstanding the contributions of this study, several limitations exist that may pave the way for future research.

First, financial planning behaviour remains in the infant stage and thus the newly established theory was limited to available evidence. In this regard, this study does not discount the possibility of extending the theory of financial planning behaviour in enriching ways, such as by adding new dimensions of the original TPB components (e.g. additional forms of perceived behavioural control).

Second, the theory of financial planning behaviour has not been empirically examined in its entirety. Thus, future research is encouraged to adopt or adapt this newly established theory in empirical investigations to ascertain its reliability, validity, and generalisability.

Third, the systematic literature review herein was limited to a single theoretical lens (TPB). As indicated through the theoretical foundation discussion, multiple theories exist to explain financial planning behaviour. In this regard, it is important to acknowledge that the development of theories in this area is continuously evolving. As other theories mature, it would be beneficial for future research to consider conducting similar reviews using those theories, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of financial planning behaviour. This could potentially uncover novel insights and lead to the development of new frameworks that could more holistically explain individuals' financial behaviours.

Fourth, the outcomes of financial planning have not been theorised. While the assumption is that good financial planning results in financial resilience, further investigation is needed to empirically verify this assumption. Further exploration of other possible outcomes is also encouraged, both at the micro-level (e.g. life satisfaction, quality of life) and at the macro-level (e.g. country happiness and financial strength).

Fifth, the relationships in the theory of financial planning behaviour are inherently linear. Nonetheless, as experience in financial planning accumulates over time, this study does not discount the possibility of a cyclical loop that reinforces the said relationships. In this regard, future research that extrapolates the theory through a longitudinal perspective is also encouraged.

Sixth, the research landscape of financial behaviour is broad and includes other aspects such as financial counselling and financial therapy. Although these areas were not covered in this study, they may be relevant in the context of the TPB and could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of financial behaviours. Thus, future research could consider investigating these areas using the TPB, which could also include other related theories, as a guiding theoretical framework. The expansion of search terms in subsequent studies would allow for a more diverse exploration of financial behaviours, potentially enhancing the generalisability and applicability of the findings. Furthermore, it may also reveal a broader range of factors influencing financial planning behaviour and related areas. Hence, researchers are encouraged to extend the current study by exploring the use of TPB alongside related theories in different areas of financial behaviour.

In closing, while this study viewed financial planning within the context of behavioural finance, it is crucial to underscore the fact that financial planning is a distinct profession with its own body of literature. Financial planning transcends the boundary of understanding and predicting individual financial behaviours. It encompasses a broad spectrum of activities, from cash flow management to estate planning, which are geared towards enhancing an individual's economic satisfaction. Each of these areas possesses a unique set of complexities and necessitates a specialised set of knowledge and skills. The profession of financial planning is dedicated to addressing these complexities and enhancing individuals' financial well-being. Our exploration of financial planning behaviour through behavioural finance should be seen as a facet of the broader, multi-dimensional discipline of financial planning. Future research should therefore endeavour to add to the rich and varied literature of financial planning to offer a more holistic and nuanced understanding of financial behaviour.

Notes

-

Based on a search for “personal finance” in the “title, abstract and keywords” and the subject area of “business, management and accounting” in Scopus on 25 December 2022.

-

Smooth consumption refers to consumption that balances or optimises spending and saving during different life phases to achieve the greatest overall standard of living (Morduch 1995).

-

Instead of Scopus or Web of Science, which are subscription-based, Google Scholar was used as the search mechanism because it is free to use and thus more accessible. Source quality can still be maintained by referring to Scimago Journal Ranks, which relies on Scopus, and Web of Science Master Journal List, albeit manually. With the journal lists acting as a cross-check mechanism and without the need for bibliometric data, Google Scholar is deemed to be adequate for the search and review. This practice is similar to that of existing reviews (e.g. Lim and Weissmann 2023; Lim et al. 2021).

-

Unlike Scopus or Web of Science, which use search string, Google Scholar use search keywords.

References

-

Agarwal, S., and B. Mazumder. 2013. Cognitive abilities and household financial decision making. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5 (1): 193–207.

-

Ajzen, I. 1985. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action control: From cognition to behavior, ed. J. Kuhl and J. Beckmann, 11–39. New York: Springer.

-

Ajzen, I. 1987. Attitudes, traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. In Advances in experimental social psychology, ed. L. Berkowitz, 1–63. New York: Academic Press.

-

Ajzen, I. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211.

-

Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein 2000. Attitudes and the attitude-behavior relation: Reasoned and automatic processes. European Review of Social Psychology 11(1): 1–33.

-

Ajzen, I. 2002. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32 (4): 665–683.

-

Ajzen, I., T. C. Brown, and F. Carvajal. 2004. Explaining the discrepancy between intentions and actions: The case of hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30(9): 1108–1121.

-

Ali, A., M.S.A. Rahman, and A. Bakar. 2014. Financial satisfaction and the influence of financial literacy in Malaysia. Social Indicators Research 120 (1): 137–156.

-

Altfest, L. 2004. Personal financial planning: Origins, developments and a plan for future direction. The American Economist 48 (2): 53–60.

-

Ameliawati, M., and R. Setiyani. 2018. The influence of financial attitude, financial socialization, and financial experience to financial management behavior with financial literacy as the mediation variable. KnE Social Sciences 3 (10): 811–832.

-

Asebedo, S.D. 2022. Theories of personal finance. In De gruyter handbook of personal finance, ed. J.E. Grable and S. Chatterjee, 67–86. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter.

-

Atkinson, A., S. McKay, S. Collard, and E. Kempson. 2007. Levels of financial capability in the UK. Public Money and Management 27 (1): 29–36.

-

Baker, H. K., K. Goyal, S. Kumar, and P. Gupta. 2023. Does financial fragility affect consumer well‐being? Evidence from COVID‐19 and the United States. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, Ahead of print.

-

Bannier, C.E., and M. Schwarz. 2018. Gender-and education-related effects of financial literacy and confidence on financial wealth. Journal of Economic Psychology 67: 66–86.

-

Bansal, H.S., and S.F. Taylor. 2002. Investigating interactive effects in the theory of planned behavior in a service-provider switching context. Psychology and Marketing 19 (5): 407–425.

-

Birari, A., and U. Patil. 2014. Spending & saving habits of youth in the city of Aurangabad. The SIJ Transactions on Industrial, Financial & Business Management 2 (3): 158–165.

-

Chan, S.C., and M.T. Lu. 2004. Understanding internet banking adoption and use behavior. Journal of Global Information Management 12 (3): 21–43.

-

Chen, H., and R.P. Volpe. 1998. An analysis of personal financial literacy among college students. Financial Services Review 7 (2): 107–128.

-

Chieffe, N., and G.K. Rakes. 1999. An integrated model for financial planning. Financial Services Review 8 (4): 261–268.

-

Christelis, D., T. Jappelli, and M. Padula. 2010. Cognitive abilities and portfolio choice. European Economic Review 54 (1): 18–38.

-

Copur, Z., and M.S. Gutter. 2019. Economic, sociological, and psychological factors of the saving behavior: Turkey case. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 40 (2): 305–322.

-

Deaton, A.S. 2005. Franco Modigliani and the life cycle theory of consumption. SSRN Electronic Journal.

-

Donthu, N., S. Kumar, D. Mukherjee, N. Pandey, and W.M. Lim. 2021. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 133: 285–296.

-

East, R. 1993. Investment decisions and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology 14 (2): 337–375.

-

Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading: Addison-Wesley.

-

Fishbein, M., and I. Ajzen. 1981. Attitudes and voting behavior: An application of the theory of reasoned action. Progress in Applied Social Psychology 1 (1): 253–313.

-

Fu, J.R., C.K. Farn, and W.P. Chao. 2006. Acceptance of electronic tax filing: A study of taxpayer intentions. Information & Management 43 (1): 109–126.

-

Fu, F.Q., K.A. Richards, D.E. Hughes, and E. Jones. 2010. Motivating salespeople to sell new products: The relative influence of attitudes, subjective norms, and self-efficacy. Journal of Marketing 74 (6): 61–76.

-

Gathergood, J. 2012. Self-control, financial literacy and consumer over-indebtedness. Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (3): 590–602.

-

Goodell, J.W., S. Kumar, W.M. Lim, and D. Pattnaik. 2021. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in finance: Identifying foundations, themes, and research clusters from bibliometric analysis. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 32: 100577.

-

Hagger, M.S., and N.L.D. Chatzisarantis. 2009. Integrating the theory of planned behaviour and self-determination theory in health behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Health Psychology 14 (2): 275–302.

-

Han, H. 2015. Travelers’ pro-environmental behavior in a green lodging context: Converging value-belief-norm theory and the theory of planned behavior. Tourism Management 47: 164–177.

-

Hanna, S.D., and S. Lindamood. 2010. Quantifying the economic benefits of personal financial planning. Financial Services Review 19 (2): 111–127.

-

Harmeling, C.M., J.W. Moffett, M.J. Arnold, and B.D. Carlson. 2016. Toward a theory of customer engagement marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 45 (3): 312–335.

-

Harris, J.D., C.E. Quatman, M.M. Manring, R.A. Siston, and D.C. Flanigan. 2014. How to write a systematic review. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 42 (11): 2761–2768.

-

Hassan, L.M., E. Shiu, and S. Parry. 2015. Addressing the cross-country applicability of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB): A structured review of multi-country TPB studies. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 15 (1): 72–86.

-

Hilgert, M.A., J.M. Hogarth, and S.G. Beverly. 2003. Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin 89: 309–322.

-

Huston, S.J. 2010. Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs 44 (2): 296–316.

-

Jamal, A.A.A., W.K. Ramlan, M.A. Karim, and Z. Osman. 2015. The effects of social influence and financial literacy on savings behavior: A study on students of higher learning institutions in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. International Journal of Business and Social Science 6 (11): 110–119.

-

Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47 (2): 263–292.

-

Kapoor, J., L. Dlabay, and R.J. Hughes. 2014. Personal finance, 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

-

Katona, G. 1975. Psychological economics. New York: Elsevier.

-

Keynes, J.M. 2016. The general theory of employment, interest, and money. Harcourt, Brace & World.

-

King, T., C. Dennis, and L.T. Wright. 2008. Myopia, customer returns and the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Marketing Management 24 (1–2): 185–203.

-

Kobbeltvedt, T., and K. Wolff. 2009. The risk-as-feelings hypothesis in atTheory-of-planned-behaviour perspective. Judgment and Decision Making 4: 567–586.

-

Kraus, S., M. Breier, W.M. Lim, M. Dabić, S. Kumar, D. Kanbach, and J.J. Ferreira. 2022. Literature reviews as independent studies: Guidelines for academic practice. Review of Managerial Science 16 (8): 2577–2595.

-

Kumar, A., J. Paul, and A.B. Unitthan. 2019. “Masstige” marketing: A review, synthesis and research agenda. Journal of Business Research 113: 384–398.

-

Kumar, S., J.J. Xiao, D. Pattnaik, W.M. Lim, and T. Rasul. 2022. Past, present and future of bank marketing: A bibliometric analysis of International journal of bank marketing (1983–2020). International Journal of Bank Marketing 40 (2): 341–383.

-

Kumar, S., D. Sharma, S. Rao, W.M. Lim, and S.K. Mangla. 2023. Past, present, and future of sustainable finance: insights from big data analytics through machine learning of scholarly research. Annals of Operations Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04410-8.

-

Kuo, N.W., and Y.Y. Dai. 2012. Applying the theory of planned behavior to predict low-carbon tourism behavior. International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction 8 (4): 45–62.

-

Lau, A., J. Yen, and P. Chau. 2001. Adoption of on-line trading in the Hong Kong financial market. Electronic Commerce Research 2: 58–65.

-

Lee, M. 2009. Understanding the behavioural intention to play online games. Online Information Review 33 (5): 849–872.

-

Lee-Partridge, J., and P.S. Ho. 2003. A retail investor's perspective on the acceptance of Internet stock trading. In 36th annual hawaii international conference on system sciences.

-

Lim, W.M., and S. Kumar. 2023. Guidelines for interpreting the results of bibliometrics analysis: A sensemaking approach. Global Business and Organizational Excellence. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.22229.

-

Lim, W.M., and M.A. Weissmann. 2023. Toward a theory of behavioral control. Journal of Strategic Marketing 31 (1): 185–211.

-

Lim, W.M., S.F. Yap, and M. Makkar. 2021. Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? Journal of Business Research 122: 534–566.

-

Lim, W.M., S. Kumar, and F. Ali. 2022a. Advancing knowledge through literature reviews: What, why, and how to contribute. The Service Industries Journal 42 (7–8): 481–513.

-

Lim, W.M., T. Rasul, S. Kumar, and M. Ala. 2022b. Past, present, and future of customer engagement. Journal of Business Research 140: 439–458.

-

Lu, J., C. Yu, C. Liu, and J.E. Yao. 2003. Technology acceptance model for wireless Internet. Internet Research 13 (3): 206–222.

-

Lusardi, A., and P. Tufano. 2009. Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. National Bureau of Economic Research.

-

Lusardi, A., and O.S. Mitchell. 2014. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 52 (1): 5–44.

-

Lyons, A.C., and U. Neelakantan. 2008. Potential and pitfalls of applying theory to the practice of financial education. Journal of Consumer Affairs 42 (1): 106–112.

-

Madinga, N.W., E.T. Maziriri, T. Chuchu, and Z. Magoda. 2022. An investigation of the impact of financial literacy and financial socialization on financial satisfaction: Mediating role of financial risk attitude. Global Journal of Emerging Market Economies 14 (1): 60–75.

-

Mahapatra, M.S., and R. Mishra. 2020. Behavioral influence and financial decision of individuals: A study on mental accounting process among Indian households. Cogent Economics & Finance 8 (1): 1827762.

-

Mahapatra, M., J. Raveendran, and A. De. 2019. Building a model on influence of behavioural and cognitive factors on personal financial planning: A study among Indian households. Global Business Review 20 (4): 996–1009.

-

Maslow, A.H. 1943. A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review 50 (4): 370–396.

-

Mathieson, K. 1991. Predicting user intentions: Comparing the technology acceptance model with the theory of planned behavior. Information Systems Research 2 (3): 173–191.

-

May, O.S. 2005. User acceptance of internet banking in Penang: A model comparison approach. Penang: University Sains Malaysia.

-

McArdle, J.J., J.P. Smith, and R. Willis. 2009. Cognition and economic outcomes in the health and retirement survey. National Bureau of Economic Research.

-

McEachan, R.R.C., M. Conner, N.J. Taylor, and R.J. Lawton. 2011. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review 5 (2): 97–144.

-

Modigliani, F., and R. Brumberg. 1954. Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In Post Keynesian economics, ed. K.K. Kurihara. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

-

Moher, D., A. Liberati, J. Tetzlaff, and D.G. Altman. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6 (7): e1000097.

-

Montaño, D.E., and D. Kasprzyk. 2015. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice, ed. K. Glanz, B.K. Rimer, and K.V. Viswanath, 95–124. New York: Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

-

Morduch, J. 1995. Income smoothing and consumption smoothing. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9 (3): 103–114.

-

Mukherjee, D., W.M. Lim, S. Kumar, and N. Donthu. 2022. Guidelines for advancing theory and practice through bibliometric research. Journal of Business Research 148: 101–115.

-

Murray, J.B., and D.J. Evers. 1989. Theory borrowing and reflectivity in interdisciplinary fields. Advances in Consumer Research 16: 647–652.

-